Three ex mayors want to get their seats back

In addition to the gubernatorial, congressional, and two county commission races, voters in some Miami-Dade municipalities will also be choosing local representatives for their town councils this November.

There are three mayoral races, in particular, that expect to be interesting for one reason or another. In all three, former mayors are trying to make a comeback.

In South Miami, the municipal offices will be on the November ballot with the rest of the ticket for the first time ever — and should positively impact turnout. Voters changed the city’s election month from February to November in 2016.

In Key Biscayne, we have a wedge issue driving votes amid a somewhat ethnically-tinged contest.

And in Palmetto Bay, we have a rematch.

Read related: Eugene Flinn tries for Palmetto Bay mayor a third time with rematch

Palmetto Bay is the only one where an incumbent is being challenged. But the challenger is definitely not a newbie. Mayor Karyn Cunningham will have to defend her seat against former and founding mayor Eugene Flinn, who she beat in 2018, 61% to 33%, after serving four years on the council. A third candidate got 6% of the vote.

What makes Flinn think that he can beat her now? Four years later, this two-way race is really a referendum on Cunningham’s performance.

The mayor has been facing increasing criticism for raising taxes twice during her tenure and for extending and doubling the franchise fee on FP&L. Cunningham also has to answer for the vacancies in the police department. And some residents are very unhappy about the 10-foot “mega sidewalks” that took out several trees on some streets.

Most recently, there are questions about the timing of some huge raises for some village employees and the sponsorships of the mayor’s Fourth of July “extravaganza,” which come from many Palmetto Bay businesses and vendors that also contribute to her campaign account.

Cunningham hasn’t been much of a success with the county either. She failed to block the controversial 87th Avenue bridge and may have lost much of her political capital trying. She could also be losing the fight to have Palmetto Bay carved out of the county’s plan to upzone the rapid transit corridor along U.S. 1. An incredibly strained relationship with the Miami-Dade District 8 Commissioner Danielle Cohen Higgins doesn’t bode well for the future.

People don’t know that Flinn can do better. But some think he might. He does remind people of a better time for Palmetto Bay.

The founding mayor from 2002 to 2010 — who also came back to serve from 2014 to 2018 — is counting on voters wanting him a third time and wanting to go back to the “original vision” for the village. Flinn, who said he was encouraged by many to run, is counting on nostalgia for the good ol’ days.

“After much thought and reflection, including listening to many of my fellow residents, I have decided to run for Mayor after it has become increasingly evident that the current administration has lost its way,” he said in a statement, adding that he would stop overdevelopment, pursue a “definite solution to our traffic challenges,” and focus on parks.

Read related: County airs 87th Avenue bridge design, details, despite Palmetto Bay dispute

“The Village’s policies run in stark contrast from the quaint, peaceful bedroom community our Village was always meant to be. It’s now being overdeveloped, overtaxed, and overburdened by bad policy decisions,” Flinn said. “My first act as Mayor will be to draw from our original vision and return to the principles that made this beautiful community one of the jewels of Miami-Dade by renewing a resident-driven form of government that engages and listens to the needs of the residents once again and not to special interests seeking to exploit it.”

In South Miami, incumbent Mayor Mary Sally Phillips is sitting it out, leaving a race between former State Rep. Javier Fernandez and former South Miami mayor Horace Feliu, who just won’t give up.

Feliu, who was mayor from 2002 to 2004 and 2006 to 2010, has run for the seat three times since, losing to former Mayor Philip Stoddard in 2016 and 2018 and to Phillips in 2020. He also ran for commissioner in 2014 against Walter Harris. He lost that, too, getting about 40% of the vote.

An adjunct professor at Fortis College, Feliu also owns a biomedical engineering company concentrating on sterilization, steam generators and other surgical equipment. And when you add his time as commissioner along with serving on the Environmental Review and Preservation Board to the three mayoral terms, he’s done 12 years in public service.

“I feel lucky to have served South Miami for over a decade and know that my experience will prove to be invaluable, if elected again,” he says on his campaign website.

“Experience matters,” Feliu says in an interview last month with Community Newspapers Publisher Michael Miller.

“I have the experience in lowering our taxes. There is not a candidate who can say the same thing,” Feliu said, adding that he was the mayor during the last housing market crash. “We didn’t reduce our services. We kept our safety and at the same time we lowered the millage rate.”

He also says in the interview that he is very much against the sale of city hall, which has been coveted by developers for years. He says he turned down Baptist Hospital when he was mayor.

“That is iconic. It is a piece of our history. And it is located in a place that, if you put a highrise, you’re going to clog Sunset Drive,” Feliu says.

“I have a track record of doing the things that are right for the citizens of South Miami,” he says.

This is Fernandez’s first attempt at a comeback after losing a Florida Senate race to Ana Maria Rodriguez in 2020, 56% to 43%, in one of at least two races where Republicans funded “NPA” plantidates to syphon votes from the Democrats. The attorney/lobbyist was first elected in a special election in May of 2018 and then kept the seat in the first regular election six months later.

“South Miami has always been the City of Pleasant Living, but its geography and rich assets also provide us with the opportunity to make it the county’s premier community to work and play in as well,” Fernandez said in a statement when he announced his candidacy earlier this year.

Read related: No surprises in Miami-Dade commission races as 3 hopefuls win

“Together, we can dramatically improve our parks and green spaces and address the emerging impacts of climate change by converting our homes from septic to sewer,” Fernandez said, adding that he believes in smart growth to build the commercial tax base.

“We must also continue to provide the highest quality public safety and city services to our residents while reducing the tax burden on our residents who are increasingly challenged by rising housing costs and escalating insurance premiums,” he said.

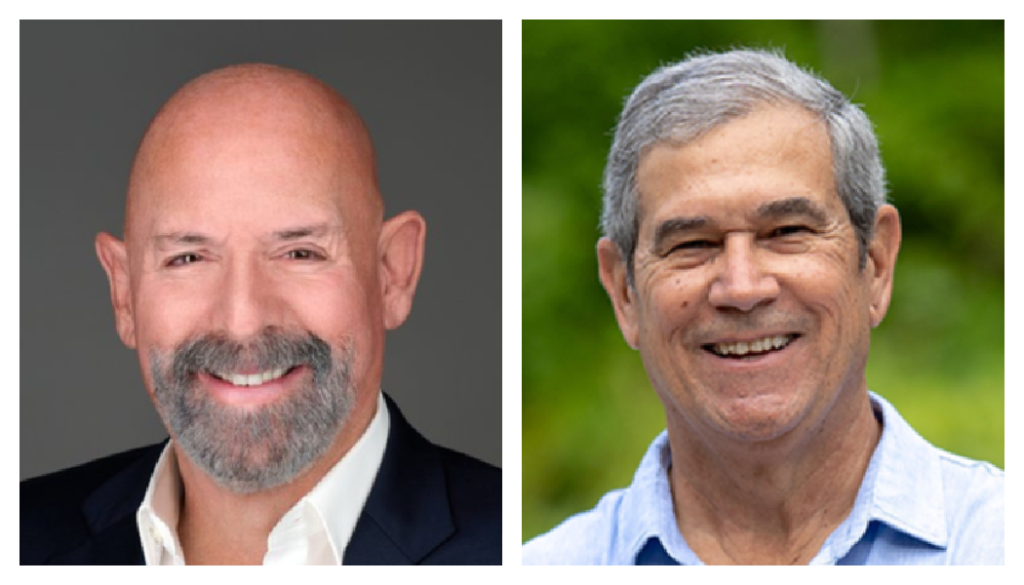

Last, but not least, there is Key Biscayne, where a nasty threeway primary ended with a November runoff between former Mayor Joe Rasco and retired lobbyist Fausto Gomez, who led the community opposition to the Rickenbacker Causeway privatization proposal last year — a plan that, apparently, won’t go away (more on that later).

Gomez is counting that the fear of a “new and improved” Plan Z for the causeway — a real estate boondoggle disguised as a safety improvement — will drive some votes in this island village of almost 8,000 registered voters his way. A little more than 3,000 voted Aug. 23.

Read related: Rickenbacker RFP looks like a done deal set-up for no-bid Plan Z proposal

But Gomez is coming in with a challenge. Former commissioner Katie Petros came in third but only four points behind Gomez. And most if not all her 793 votes will likely go to Rasco in round 2.

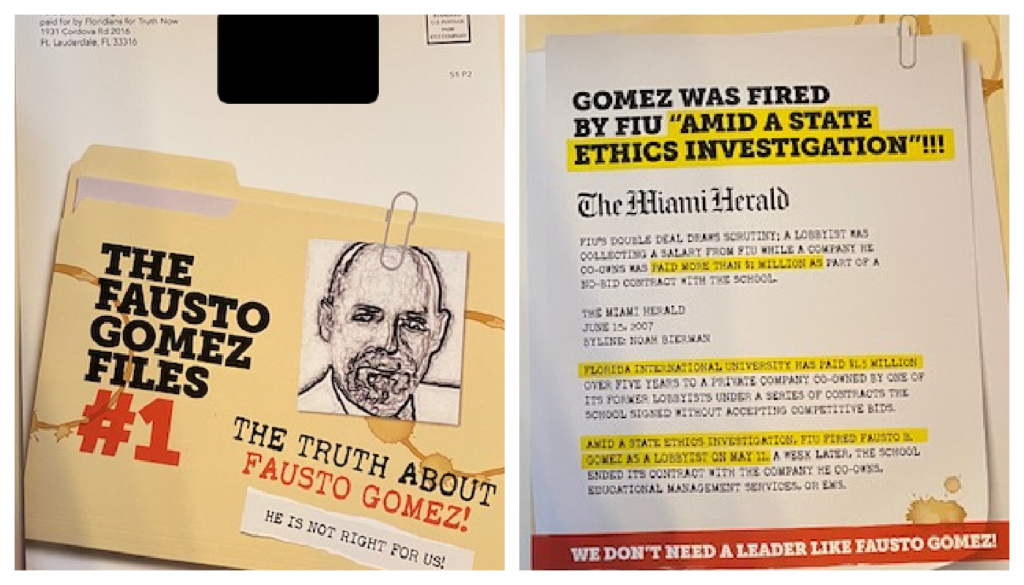

Also, the first round got nasty with a whisper campaign against Gomez “or the Cubans will take over” — even though Jose Ignacio Rasco could be Cuban, too — and mailers from a political action committee that brought up an old ethics complaint about a conflict of interest when he was the lobbyist for Florida International University.

The “He is not right for us” tagline had a double meaning.

Gomez says he is proud of his political scars, which he explains in detail on his website. “Apparently the proponents of other candidates have so little confidence in them that their strategy is to try to tear me down,” he said.

He is self-funding his campaign so he won’t be beholden to anyone, he says. Meanwhile, there is a lot of outside money in Rasco’s campaign.

But Rasco is a known entity. He was mayor from 1998 to 2002, and yes, that was a long time ago. He is the establishment choice and has the endorsement of current mayor Michael “Mike” Davey. Rasco was also the director of the Miami-Dade Intergovernmental Affairs department, which could be a plus at a time when the village is having strained relations with both the county and the city of Miami governments. He is also on the Virginia Key Advisory Board.

But where was Rasco when Miami-Dade tried to jam a $400-million Plan Z to turn the Key’s only driveway in and out for 15,000 residents into a linear park with amenities? Ladra doesn’t remember him being part of the loud opposition. But Gomez was front and center in the fight that ultimately derailed the plan — at least temporarily.

There should be debates between the mayoral candidates in all these races before absentee or vote-by-mail ballots are sent in mid October.